Case 1

This is a normal frontal view of the chest, a chest radiograph or chest X-ray (CXR for short).

Question 1:

a) "Frontal" can be used for any view like this, whether it was obtained AP or PA. Which frontal view is preferred and why?

We prefer to use a PA view, which minimizes the geometric distortion of the cardiac silhouette. Because an x-ray beam is divergent, structures that are farther from the receptor (like the heart on an AP projection) are magnified on the image. Since we want to assess heart size precisely, we therefore prefer a PA view.

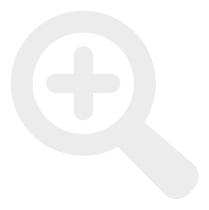

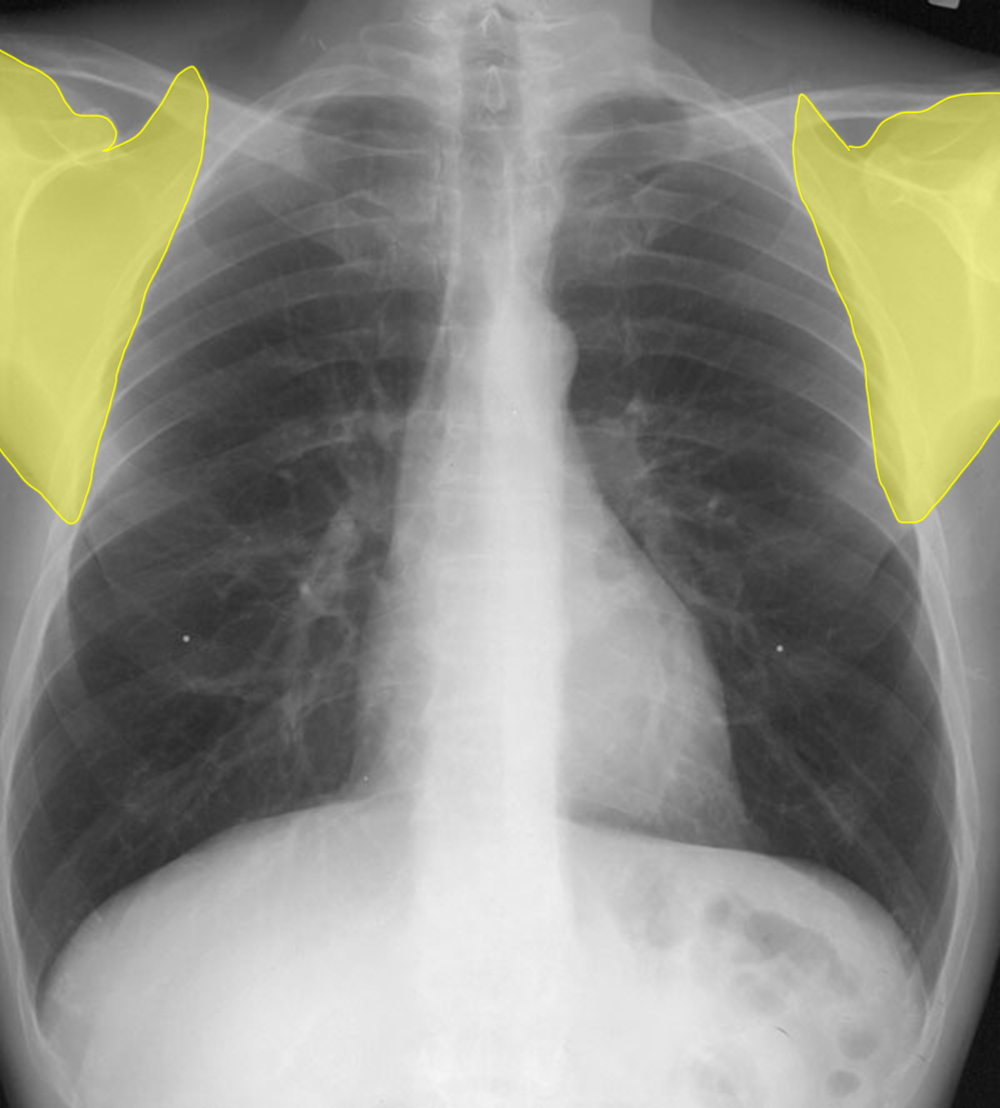

b) How can scapular position can be helpful in telling an AP from a PA view?

For a PA view, the patient must be able to stand on their own (at least for the amount of time it takes for the technologist to expose the image), and they are asked to rotate their shoulders to move the scapulae laterally, ideally past the ribcage. For this maneuver, they can put their hands on their hips and roll their shoulders anteriorly, or they may grasp a bar on the far side of the receptor stand, which results in lateral movement of the scapula. Actually, most images viewed digitally will have a label indicating the projection, but this varies a bit from system to system and viewing station to viewing station.

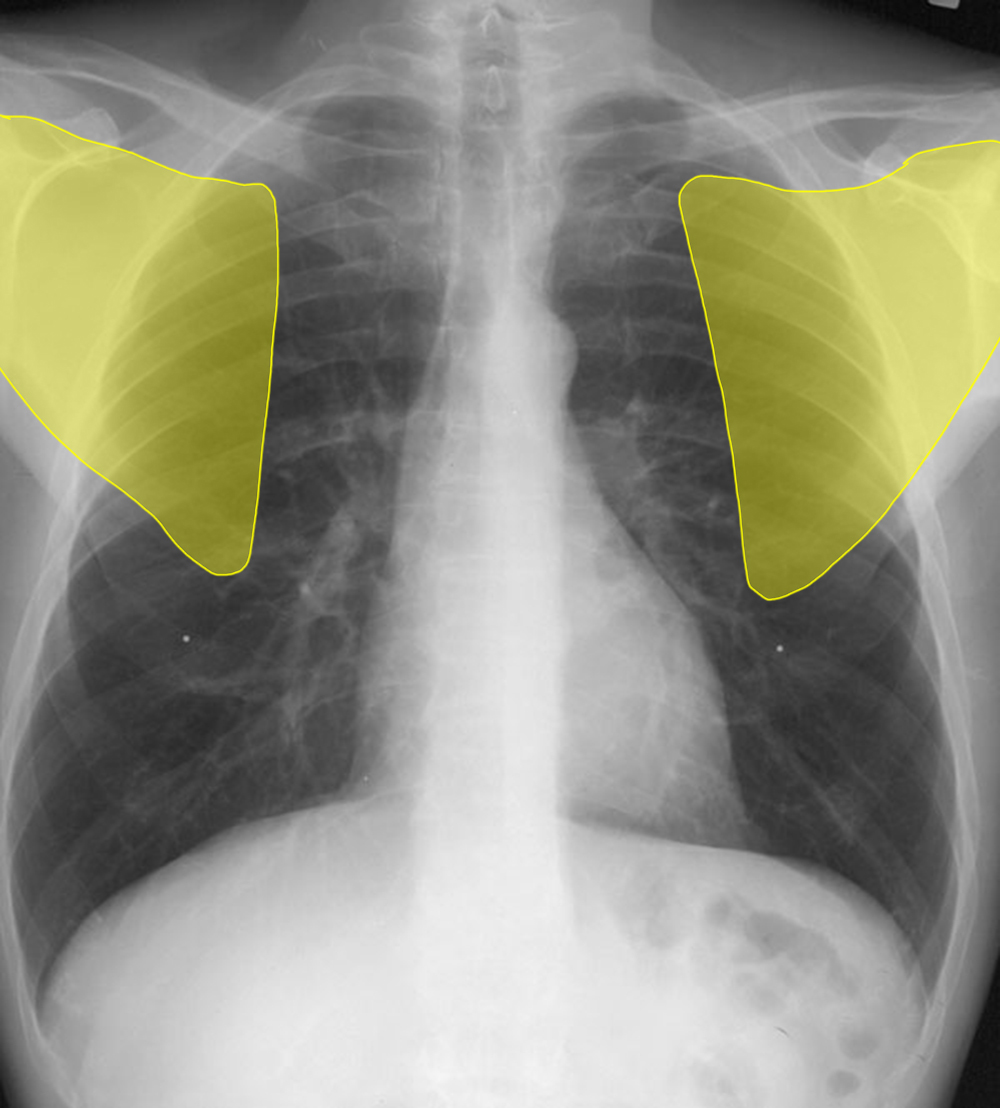

c) Another technical factor to consider is the brightness or darkness of the image, called 'exposure' or 'penetration. How can you assess this technical factor?

Check the appearance of the thoracic spine. You can faintly make out the edges of many of the thoracic vertebrae and some of the disc spaces. This usually indicates correct exposure.

Question 2:

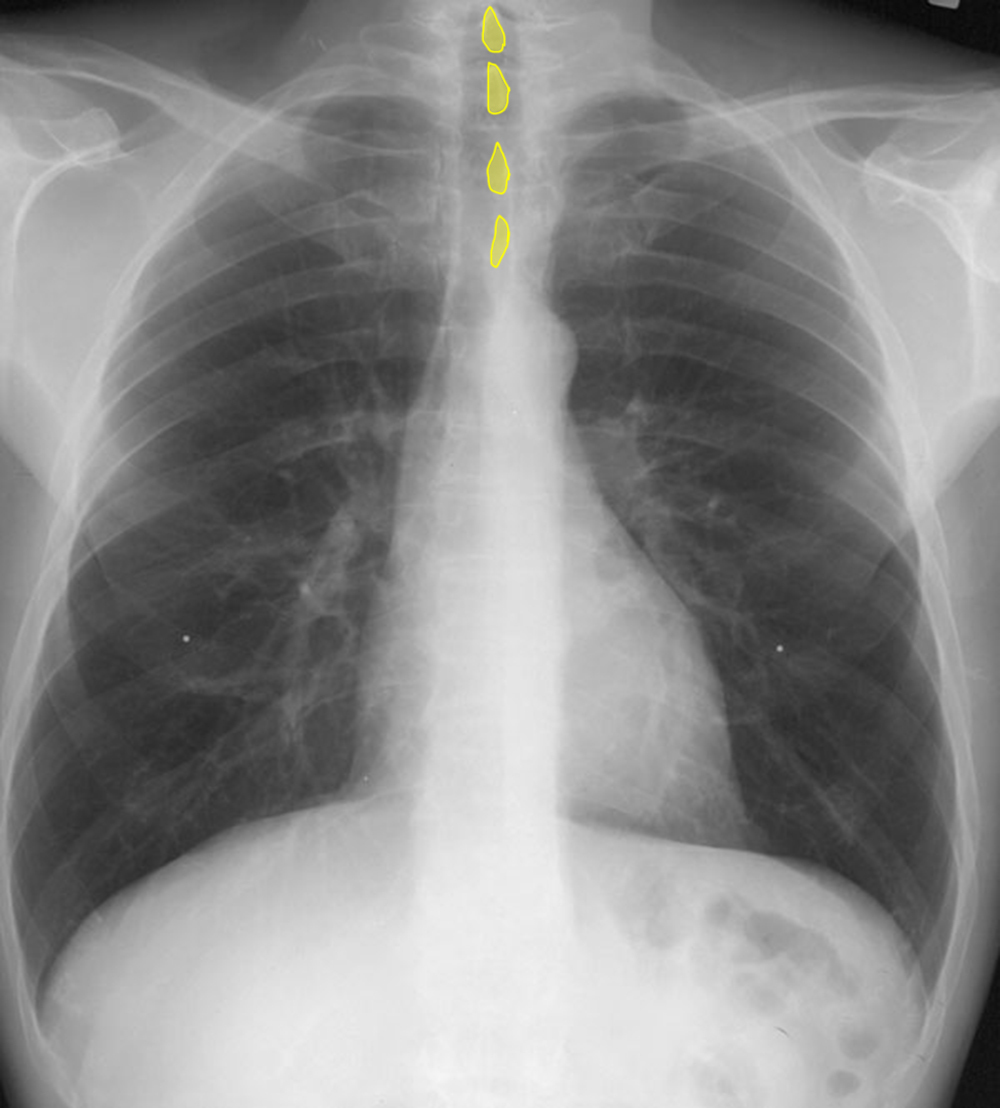

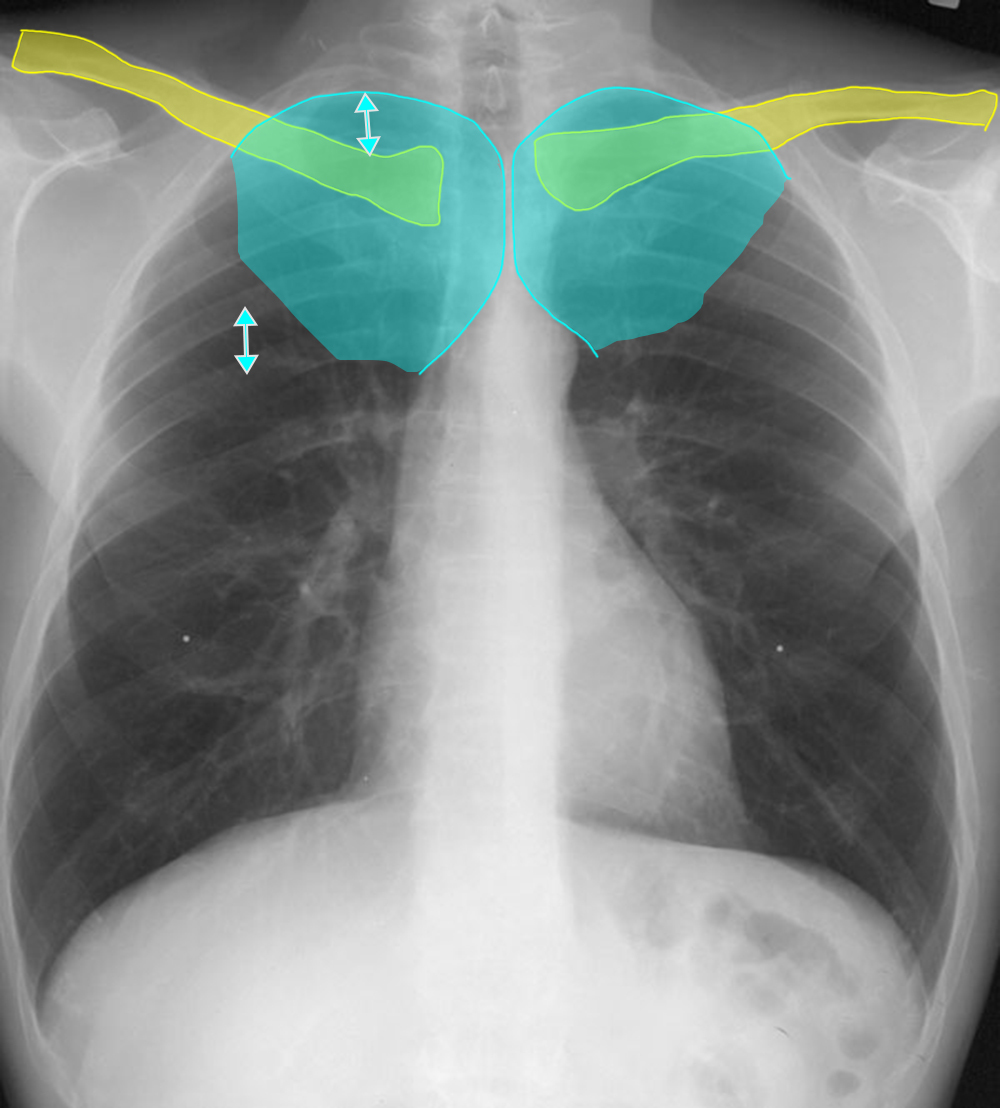

a) Check the labels below for illustration of how to detect rotation in the axial plane (around the axis of the spine, using spinous processes and clavicles). How is this assessed?

On a non-rotated frontal view (either AP or PA), the upper spinous processes are usually easy to see as they are pointing directly backward, so are visible end-on. They are obviously far in the posterior part of the chest. The clavicular heads are also usually easy to see and are far in the anterior part of the chest. If the patient is not rotated, the spinous processes should be right in the middle position between the clavicular heads.

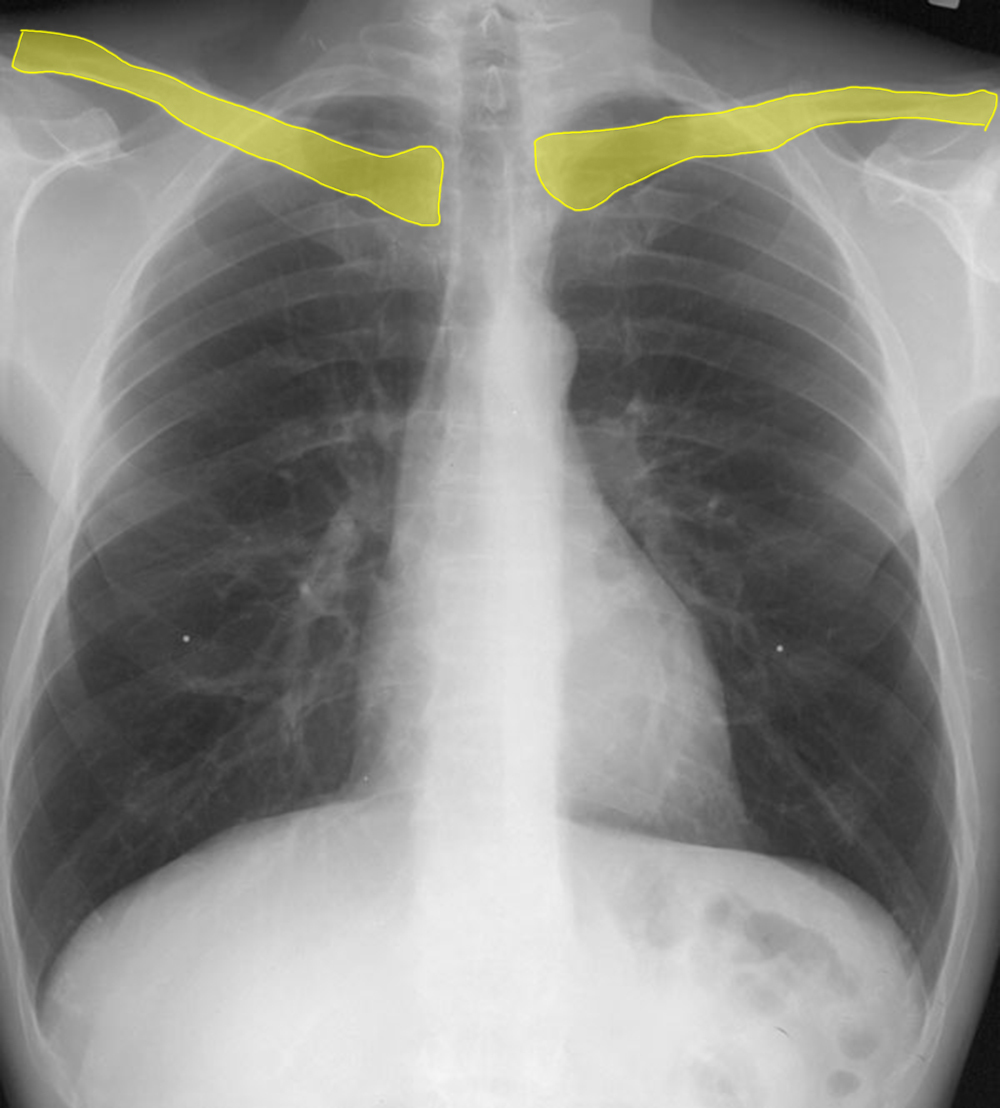

b) Check the labels below for illustration of how to detect rotation in the sagittal plane (forward or backward, ie. lordosis or kyphosis). How is this assessed?

As noted above, the clavicles are far anterior in the chest, and run in a fairly horizontal plane on the frontal view. There is usually a bit of lung visible above them. This lung is actually fairly far posterior in position. So if the patient is in kyphotic position (bending or slumping forward), there will be MORE lung visible above the clavicles than normal. If the patient is in lordotic position (bending or slumping backward), there will be LESS lung visible. The normal amount is about the same as the distance from one posterior rib to the next. This is not a very precise measure but just something to give a rough estimate and correct for body size.

Question 3:

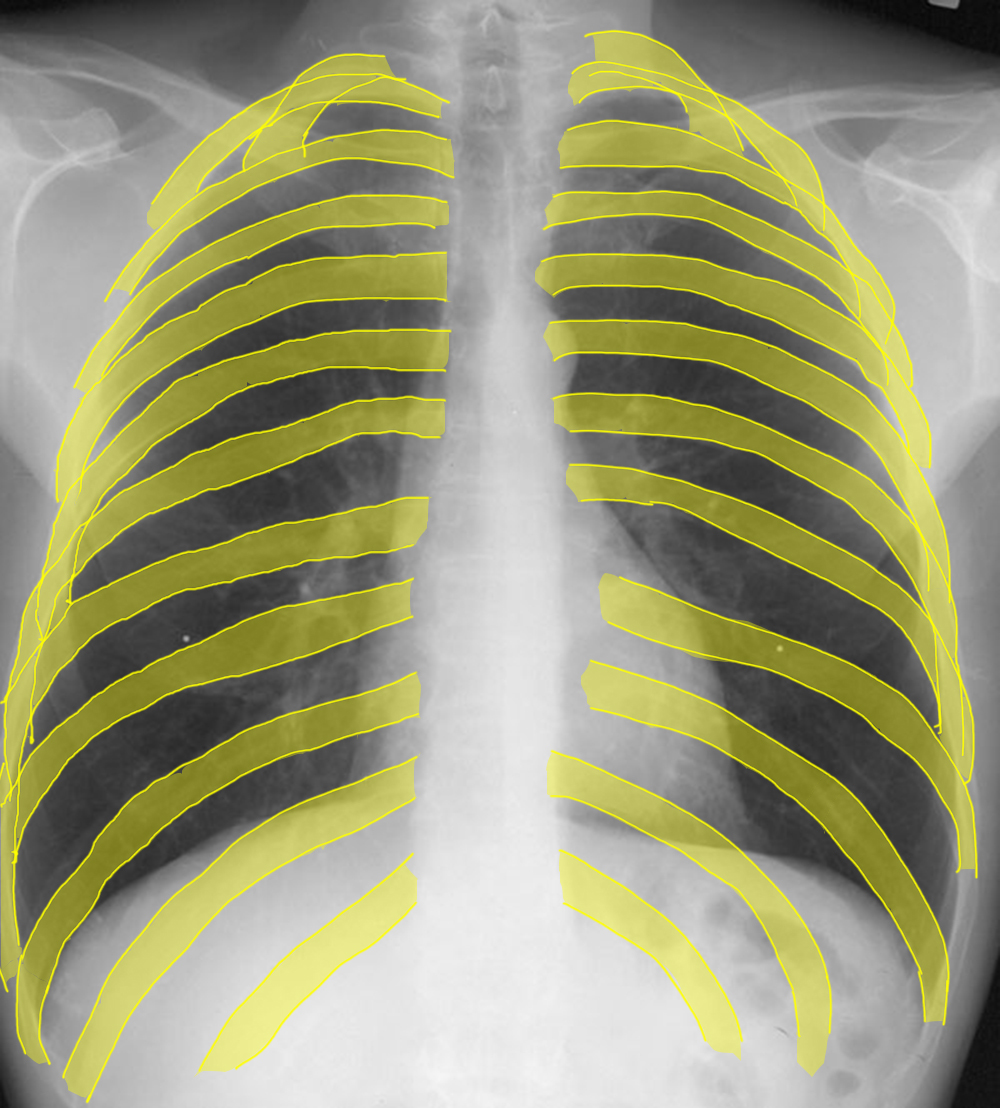

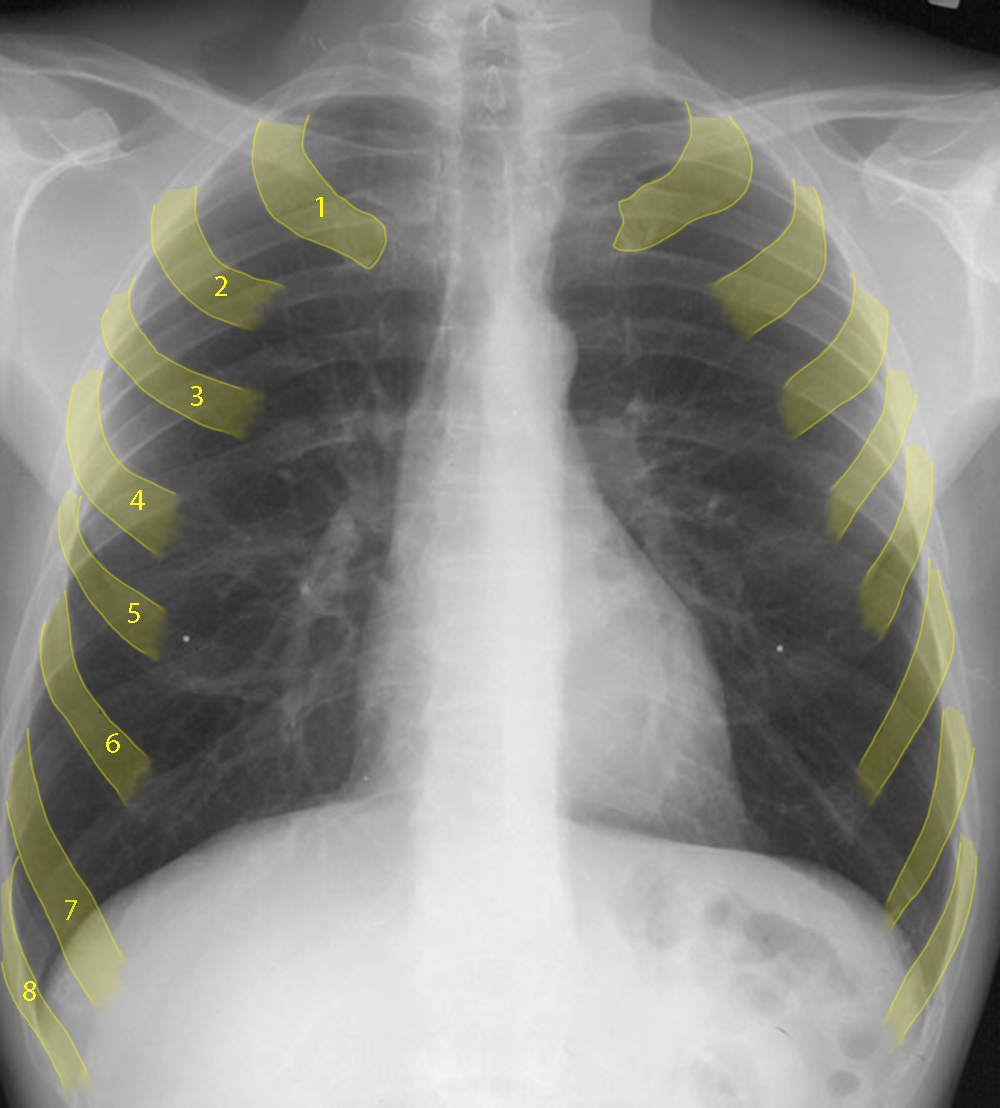

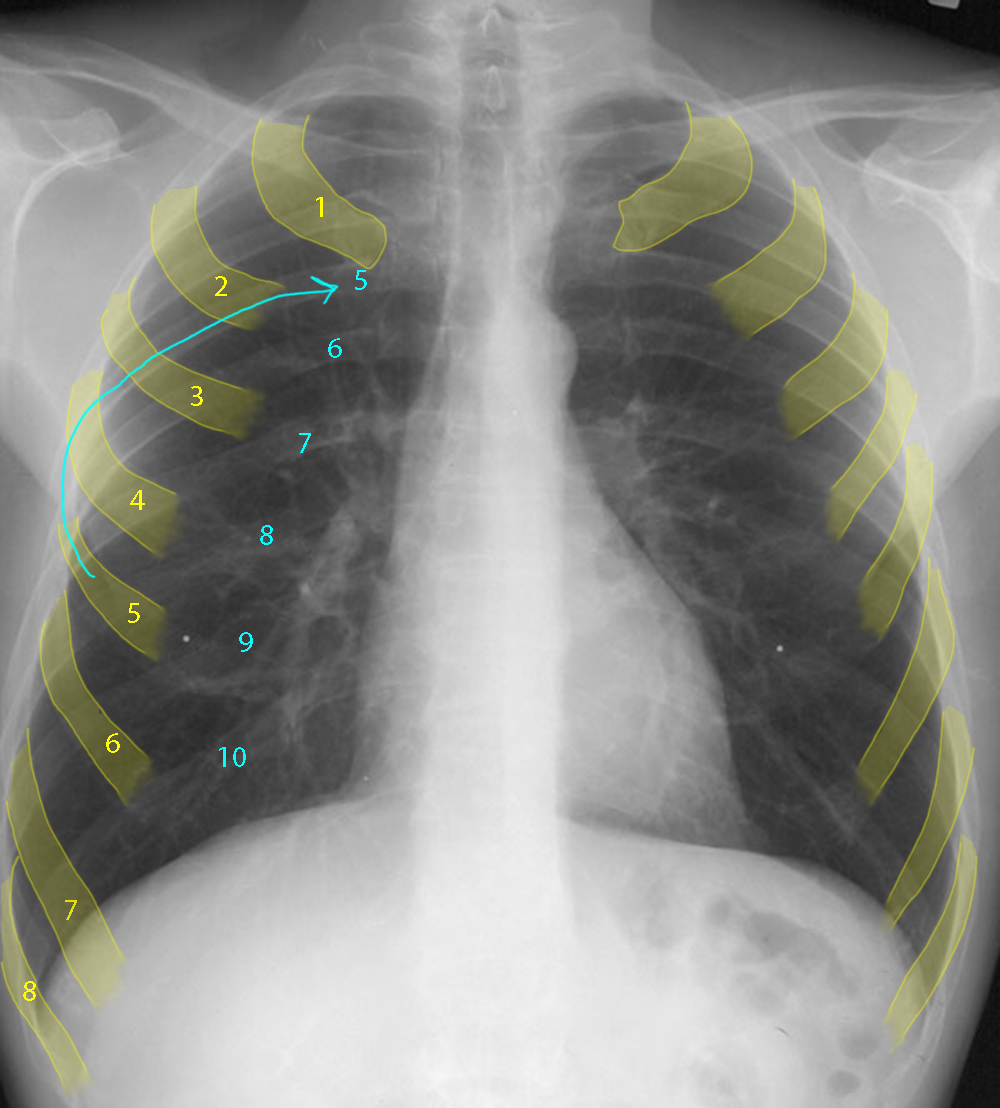

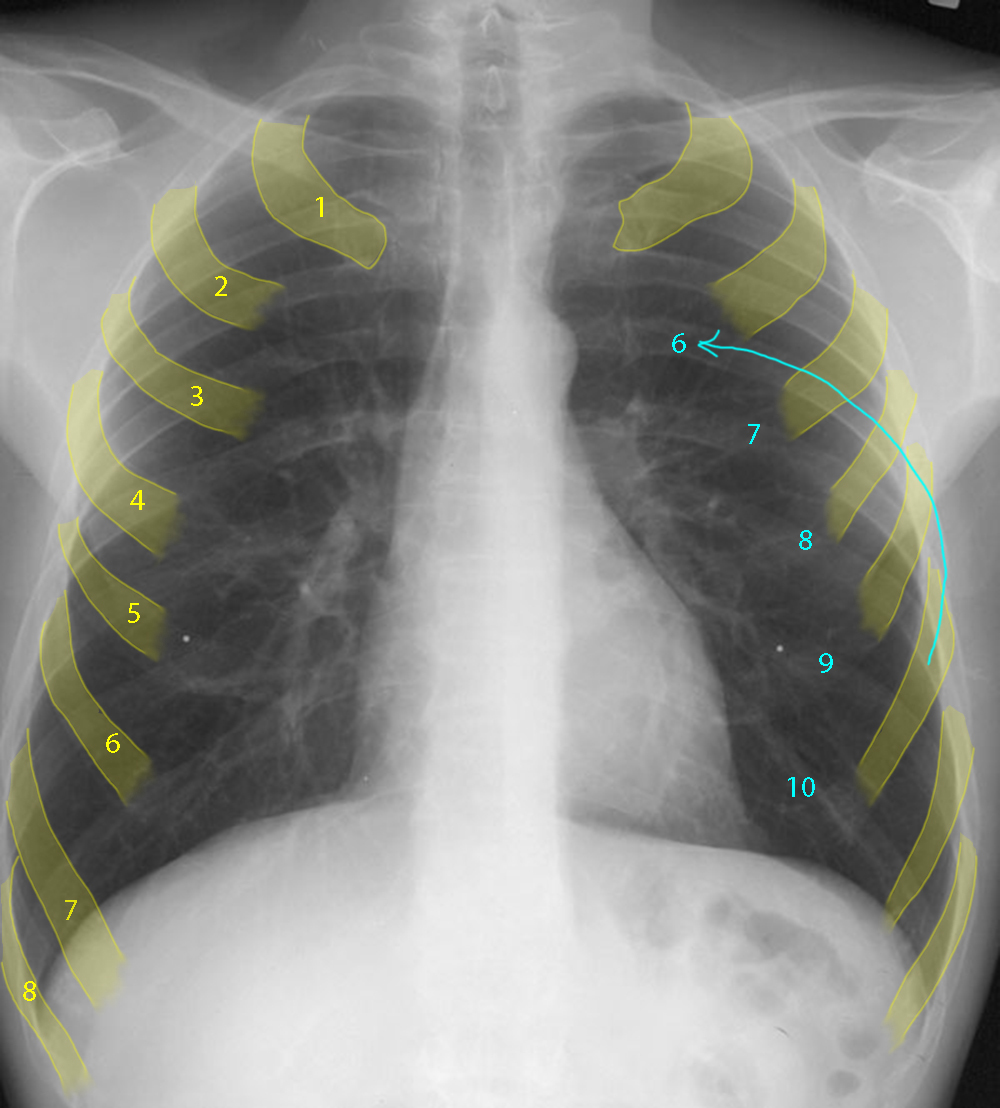

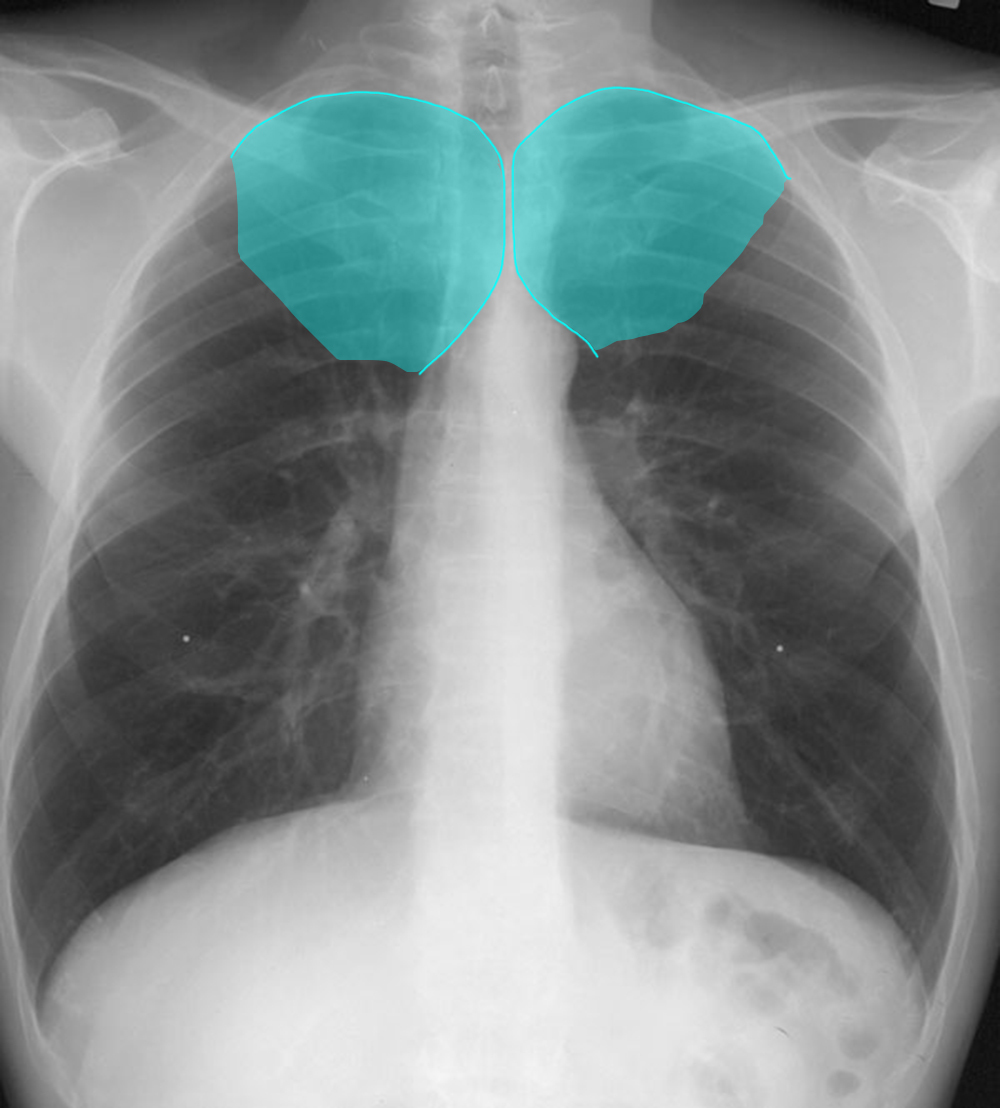

Another technical factor to check on every CXR is the level of inspiration. This can be roughly done by just eyeballing if the lungs look taller than wide, but if you want to be more precise, you can count ribs. Check the labels below for a method to make rib counting easier. What makes counting posterior ribs from top to bottom hard?

In a normal level of inspiration, you should see about 10 posterior ribs above the diaphragms, and posterior ribs are overall easier to see than anterior ribs, which are partly cartilaginous and rather faint. However, the upper 2-3 posterior ribs are often projected on top of one another on the frontal view, so it is easy to make a mistake in counting them. For that reason, it is often better to start counting anterior ribs, and once you are low enough to feel confident that you can follow one of them around to its posterior portion, then you can continue on down counting posterior ribs. This takes a bit of practice.